March, 1860. Abraham Lincoln considers an invitation to Hartford, determined to widen his appeal as a possible presidential candidate. “Do not fail, for the sake of Connecticut,” his anxious host writes in anticipation.

March, 1860. Abraham Lincoln considers an invitation to Hartford, determined to widen his appeal as a possible presidential candidate. “Do not fail, for the sake of Connecticut,” his anxious host writes in anticipation.

On that cold winter night of March 5th, Honest Abe does not disappoint. He speaks to a packed house at Hartford City Hall, located on Market and Kingsley Streets. It’s only a week after his triumphant New York appearance that for all practical purposes has established him as a serious contender for the top of the Republican ticket. Lincoln’s speech is about labor: first and foremost the three million enslaved Black men women and children who live in bondage on southern plantations. But he also speaks of “free labor”– the factory workers who now outnumber the self-employed farmers across the young country, and especially the Massachusetts shoe workers who have just organized a massive strike.

Lincoln doesn’t talk in political or economic terms; he places his remarks in a moral framework. He argues that our country will be stronger when we respect black and white workers alike, because, as he says in a unique turn of phrase, “RIGHT makes MIGHT.”

Lincoln doesn’t talk in political or economic terms; he places his remarks in a moral framework. He argues that our country will be stronger when we respect black and white workers alike, because, as he says in a unique turn of phrase, “RIGHT makes MIGHT.”

In New England these days it takes almost $11 a week to support a family, but the striking shoe workers earn a mere $12 a month. And factory work is dangerous. On his way to Hartford, Lincoln has just stopped at the site of the country’s worst-ever industrial accident at the Pemberton Mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts. When the mill collapsed in January, more than 145 workers were buried alive or burned to death, with another 166 injured. The disaster could have been prevented: building construction was faulty and the boss overloaded the top floors with heavy machinery to increase profit. Lincoln saw the devastation and wrote home about it.

Now, Lincoln provides a firm defense of the two-week old shoe workers’ walkout: “I know one thing- there is a strike! And I am glad to know that there is a system of labor where the laborer can strike if he wants to! I would to God that such a system prevailed all over the world.”

Not long after, thousands of the workers return to their jobs with raises, and in at least thirty shoe factories, with legal contracts that protect their gains.

Four years after Lincoln’s support for the shoemakers’ strike, union printers in St. Louis walk off their jobs. Federal soldiers are brought in to break their strike. The printers write to President Lincoln, reminding him of the words he had spoken in Hartford. Lincoln orders the troops to be withdrawn, declaring that the government “should not interfere with the demands of labor.”

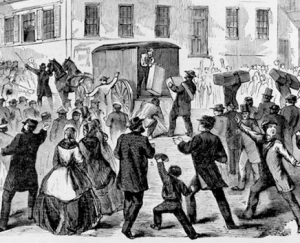

Hartford is alive with debate and activity on the slave issue. Over the past decade Connecticut has outlawed the hated institution within its borders; abolitionists outwit professional slave catchers and transport slaves to safety; Harriet Beecher Stowe publishes Uncle Tom’s Cabin (the best-selling novel of the 19th century); the General Assembly passes a state law that largely nullifies the infamous Fugitive Slave Act; fiery abolitionist John Brown has been in town to raise funds for the slave rebellion he is secretly planning at Harper’s Ferry in Virginia.

Still, some white wage earners see black men as a threat to their livelihoods. Lincoln disagrees: he tells his Hartford audience “The proposition that there is a struggle between the white man and the negro is a falsehood. It assumes that unless the white man enslaves the negro, the negro will enslave the white man,” an assumption that Lincoln says is dead wrong.

The 1860 slavery debate is also the story of two Hartford men named Sam. One is Samuel Colt, the gun maker who profits by selling arms to both North and South. He has recently sponsored a pro-South rally at City Hall where one featured speaker rails against the abolitionists and charges that “the lovers of negroes become the haters of white men.”

The other is Sampson Easton, a livery driver and free black man who lives near Front Street. On December 2, 1859, the night of John Brown’s execution for the deadly Harpers’ Ferry raid, Easton sneaks into the State House on Main Street with a lantern and yards of black cloth. Climbing toward the roof, he drapes the “madam justice” statue in mourning. Easton is caught and prosecuted for his crime. Months later, Colt continues to make millions and sends off his last gun shipment to the South.

Abraham Lincoln’s appearance in our city helps anti-slavery Republicans capture the governor’s seat in April, traveling to New Haven, Meriden Norwich. He decisively wins Connecticut in the November presidential election, beating out the fractured Democratic Party. The Hartford Courant reports a rainbow appearing over the city on election day. But storm clouds are brewing across the nation as Southern states prepare to secede. As he leads the country toward its destiny, Lincoln calls slavery “a war on the rights of all working people.”