Ethel Thompson and her family reached Hartford after midnight. She entered the Hotel Essex on Main Street and went to the front desk to check in. The night clerk got the key and was taking her to a room when she mentioned that she, her husband and their small grandchild were “colored.”

Ethel Thompson and her family reached Hartford after midnight. She entered the Hotel Essex on Main Street and went to the front desk to check in. The night clerk got the key and was taking her to a room when she mentioned that she, her husband and their small grandchild were “colored.”

The clerk stopped. The light-skinned, blue-eyed woman had taken him by surprise. And now, the clerk told Mrs. Thompson, there just happened to be no room for her family at the Hotel Essex.

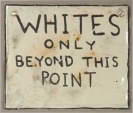

It was July 4, 1945. Ethel Thompson had one son in the Army, serving in the  Philippines. Her step-son was serving in Germany. But these facts could not help Thompson cross the color barrier. The family wandered around until it was morning and they could call on local family members. Then Ethel Thompson went to the Hartford Police Station to swear out a complaint.

Philippines. Her step-son was serving in Germany. But these facts could not help Thompson cross the color barrier. The family wandered around until it was morning and they could call on local family members. Then Ethel Thompson went to the Hartford Police Station to swear out a complaint.

The hotel clerk’s arrest was the first prosecution in the state for violating a 1941 Connecticut law that banned discrimination by hotels or other public conveniences against any person because of their race or color.

At the trial, the defense produced witnesses who backed up the clerk and testified that other Negroes had stayed at the hotel in the past. But the police detective’s testimony seemed to tell a different story. In the course of his investigation, the cop took a statement from the offending clerk. The detective asked him why he had refused Mrs. Thompson a room. “Just one of those things,” the clerk replied.

At the trial, the defense produced witnesses who backed up the clerk and testified that other Negroes had stayed at the hotel in the past. But the police detective’s testimony seemed to tell a different story. In the course of his investigation, the cop took a statement from the offending clerk. The detective asked him why he had refused Mrs. Thompson a room. “Just one of those things,” the clerk replied.

The judge found the hotel clerk not guilty. The Honorable Abraham A. Ribicoff  told the courtroom that he knew there was discrimination in Hartford, but the state had not proven its case.

told the courtroom that he knew there was discrimination in Hartford, but the state had not proven its case.

The new civil rights movement was just beginning in Hartford. Racial bias was being forced from the shadows.