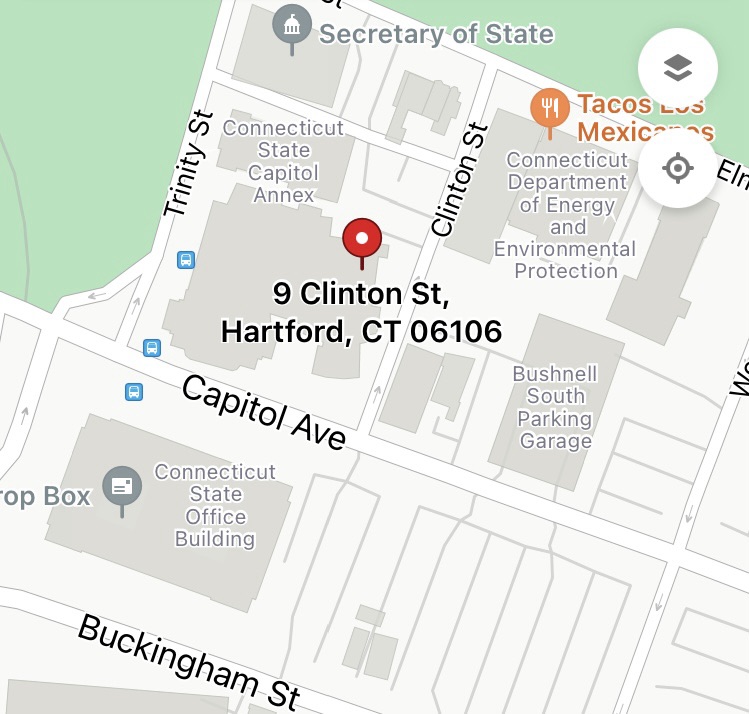

Ernie Fiorillo and his daughter Patricia Fiorillo were informed on April 5, 1980 that their 65-year-old building was slated for demolition. Pat had been living there her entire life. The reason for their eviction? The apartments at 9 Clinton Street were owned by Bushnell Memorial Hall. The corporation’s managing director Leland S. Jamieson, Jr. stated that the many electrical, plumbing and structural problems were too expensive to repair. That was Jamieson’s first lie.

The Clinton Street building was a Hartford neighborhood in miniature. It housed 54 rental units, a florist shop, and Stage Two, a small diner. Pat Fiorillo worked for Aetna Insurance at the time of the battle with Bushnell. As Pat described it, part of her job was to train new hires, who were then promoted over her head, above her pay grade.

The tenants of the 9 Clinton Street building, owned by Bushnell were told they had thirty days to move or lose their property. That was Jamieson’s second lie. As tenant advocates promptly informed the neighbors, state law required at least three months notice before forced eviction.

Jamieson stated that the Bushnell was losing money on the investment they had bought in 1971. The implication was that the tenants were not paying enough rent to cover maintenance costs. Another lie. If the Bushnell corporation was in the red, it was because the apartments were kept vacant: 27 of the 54 units were empty. Virtually every reason Jamieson gave to evict the Clinton neighborhood and demolish the apartment house was an excuse.

The Bushnell’s decision came at a time when Hartford was suffering a severe housing shortage. The city’s rental vacancy rate was estimated to be less than 1%. The lack of affordable housing was so bad that Mayor George Athanson declared a city-wide state of emergency.

Two neighborhood activist groups– Homefront and the Citizens Lobby– came to the tenants’ aid, helping them build a campaign to save their homes. They lobbied city officials, researched the truth behind Jamieson’s claims, held vigils, picketed, and leafleted Bushnell events. They steered the tenants toward the state’s housing court to seek relief from the evictions. They believed that as a tax exempt organization receiving city services, the Bushnell had a special responsibility to avoid worsening the severe housing crisis.

Hartford City Councilwoman Olga W. Thompson, chair of the council housing committee, announced she opposed the displacement. “We are trying to save existing properties as often as we can,” Thompson told the press. The entire city council then voted to find a way to protect the building.

Public pressure increased when a vacancy occurred on the Bushnell Board of Directors. Advocates demanded Pat Fiorillo be named as a trustee with voting rights. Leland Jamieson said he had not heard about the appointment and that “it’s not my position to judge.” Pat replied “I think it will do some good for the trustees to hear firsthand how we tenants feel,”

The Hartford Architecture Conservancy informed the Bushnell, after a professional inspection, that the building could be repaired with minimal or no rent increases– and better management. The Conservancy stated that the plumbing cross-connections were similar to “thousands of other city buildings, but they’ve existed with no reported cases of public health problems.”

In its report the group said “our inspection suggests that possibly no rehabilitation at all would be necessary to operate the building safely for an indefinite time. Better management and maintenance would go a long way to rectify in the problems of this building.” In fact, the tenants claimed, building upkeep suffered when Bushnell bought it and replaced the existing contractor.

The Knox Foundation offered to work with the Bushnell to save the apartments and was looking to appropriate $50,000 for the project, according to the director Reverend David McDonald.

Nine state legislators joined the fight for 9 Clinton Street. Since the state of Connecticut allowed Bushnell patrons to park in the massive state employee lot at no cost, the lawmakers were looking into the possibility of ending that practice. According to the elected officials, “Clinton Street is a very good site for the many elderly people who live there.“

But the pressure to move was on for the remaining tenants. One occupant, a tool maker at Colt Firearms, could only find an apartment twice the cost as his Clinton Street home. Despite Bushnell director Jamieson’s claims, tenants denied they had been offered relocation assistance.

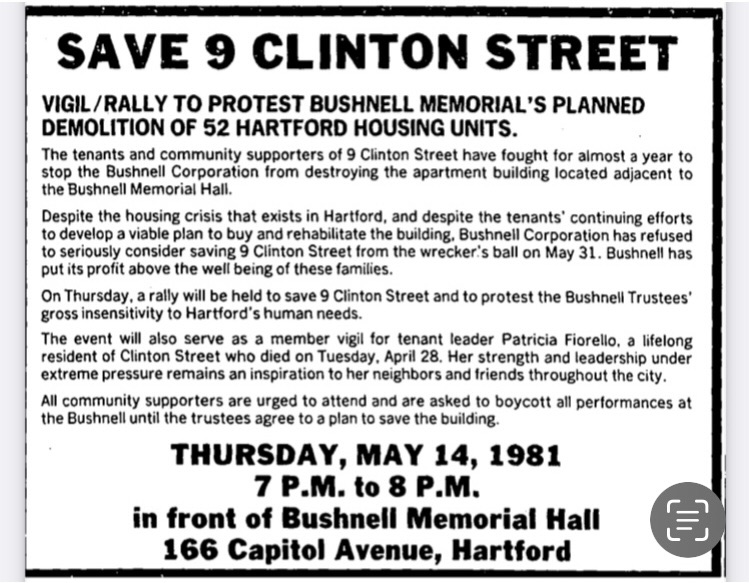

Just one year after the Clinton Street tenants began their fight to save their homes, their leader Pat Fiorillo died of a heart attack.

On May 14, 1981 tenants and their supporters protested at a Bushnell performance. “We want to hit them where they live like they hit us where we live,” said tenant B.J. Reardin.

Inside the hall, two protesters mounted the stage before the curtain was raised, unfurling a banner that said “Consider The Victims, Save 9 Clinton St.” They briefly addressed the audience before being hustled out by Bushnell personnel. John Bach told the crowd they did not want to disrupt the performance but felt they could no longer be silent. When asked for a comment, Jamieson said “we don’t feel there’s a crisis.”

On June 3, 1981 the last of the tenants left Clinton Street. Despite the residents’ continuing efforts to develop a viable plan to buy and rehabilitate the building, Bushnell refused to seriously consider saving 9 Clinton Street from the wrecker’s ball. “The corporation has put its profit above the well-being of these families,” one tenant supporter said.