WE will never be able to measure the financial waste, false hopes and human pain caused by relentless race and class discrimination in Hartford. Real estate businesses, banks, insurance companies and powerful politicians have–at least since the 1930s–conspired to create hidden policies that keep the races apart.

Through racist practice, law, and government edict, these policies include redlining, disinvestment, and the refusal to insure Black and Brown communities. The construction of physical barriers has also been employed to restrict movement between neighborhoods and to blunt the progress of poor and working people.

When people outside of Hartford are asked to describe in a single image how they picture the city, they usually mention the skyline of Downtown: Travelers Insurance, the Boat building, the Gold building. Or they think of the so-called “inner-city”: broken buildings and impoverished residents. But neither gives us an accurate picture of this city of 120,000 people.

Over the last 75 years, Hartford’s manufacturing industry has disappeared. It has run away to low-wage states or poor countries in order to increase their profits and escape unions, avoid worker protections, living wages or health and safety protections. That’s why the overwhelming number of people who live in the city are stuck in the service or domestic industries, on the lowest salary rung.

Hartford has always been the home of poor and working people. Neither government nor business has ever paid attention to the neighborhoods, except when they create turmoil. The 1960s exemplified the “boiling over” of the city’s Black and Puerto Rican communities—rebellions of rage.

At the start of the Great Depression, no city or state legislation supported the unemployed, the hungry, or the homeless. It was only when urban movements collectively forced the federal government, through the New Deal, that Hartford and the nation responded with pro-people policies affecting millions of families.

In the end, big business projects like Constitution Plaza (above) have failed. They promised to become the center of fashionable shopping, the headquarters of the Chamber of Commerce, upscale restaurants, bookstores and a hotel. There were even plans to build a heliport and two Playboy clubs. It was a short-lived promise, and today the Plaza remains a largely empty, barren concrete and granite monument to corporate waste.

By the 1950s, Hartford’s insurance companies and banks were motivated to address large pockets of the poor, particularly on the Front Street east side of downtown along the Connecticut River, and the North End of the city. Ignoring poor people was no longer an option, and raising living standards too expensive. The best remedy, they argued, was to demolish neighborhoods and attract high-income people who already enjoy many other housing options in the region.

From these efforts came a secretive planning group of Hartford’s elite. They were known as The Bishops.

===================================

Front Street/ Little Italy 1958

James H. Kinsella served as mayor of Hartford when the 1958 destruction of the Front Street neighborhood was initiated.

At the opening demolition ceremony, he picked up a brick and threw it through the window of an abandoned building, shattering the glass.

The rich and powerful had a plan for Hartford: “eliminate” poverty by pushing people out of the city and out of sight. They called it redevelopment or urban renewal. Both phrases seemed harmless enough, with the promise of a cleaner, better city.

“Constitution Plaza started a ripple effect that led to many of the problems of Hartford’s north end. [When] it went up, black people in the area were squashed and squeezed in the north end…because of racist real estate agents. The riots of the 1960s were the outgrowth of blatant racism caused in part by the separation of neighborhoods resulting from Constitution Plaza.”

-Boyd Hinds, director, SAND Enterprises

Travelers Insurance Company, the major force behind this effort, planned to build 1500 replacement housing units north of Front Street, but then decided that being a landlord was too much of a “bother” and a “headache” (their words).

=========================

Constitution Plaza, 1959

The crowning achievement of this corporate renewal project was Constitution Plaza, which spans almost the length of the entire neighborhood from Morgan to Grove Streets. Today, the Front Street neighborhood can only be reached by one “down” stairway. Otherwise, people have to brave the highway traffic at both ends of the Plaza in order to travel east.

“The concept of the government taking over private property (under eminent domain) and selling it to a private entity, to be used for other than a public purpose, was very difficult to overcome.”

–Former Hartford mayor James Kinsella

Dominic “Nicky” LaTorre was the last business owner on Front Street. He operated the Connecticut Live Poultry Store for 56 years. LaTorre refused an offer of $110,000 in 1969 for his property so Travelers could build a $20 million expansion. Dominic LaTorre died in March, 1983, without having surrendered his business. The store was run as a deli by his children until 1990.

“Who the hell was I but a little chicken man trying to make an existence?’

–Nicky LaTorre

=========================

Greater Hartford Process, 1975

–The Bishops headed up the “overlapping, interlocking, and powerful” political and economic network in Hartford.

-Boyd Hinds, civil rights activist

A confidential memorandum written by the big business-funded think-tank Hartford Process was leaked in January, 1975. It boiled down to four blunt directives: accept that “the ghetto will remain”; halt Puerto Rican immigration; protect Downtown with “land banks” and bulldoze open spaces to keep poor neighborhoods at a distance.

In addition, Process decided to build a new town near Coventry, Connecticut, with the idea that poor people would move there, out of the city.

Needless to say, the confidential Process document outraged Hartford’s neighborhoods and spelled doom for this dystopian experiment.

[Opposing Hartford Process] “is like using a slingshot against a Sherman tank. But if you throw a big enough rock in the tank-tread, it will stop.”–Antonio Soto, director of La Casa de Puerto Rico

“This is clearly for the benefit of the suburbanites who will drive to their office jobs and never have to set foot on Hartford streets or mingle with Hartford residents.” -Marcia Bok, UConn School of Social Work

=========================

Congress Street, 1976

Even though Process was seriously wounded by this multi-million dollar boondoggle, one piece of the project was pushed forward. Urban planners and their corporate benefactors were not about to give up.

Congress Street was an old city neighborhood where families had been living for as long as 35 years. The buildings were sold to a developer who then forced every single tenant out, to be replaced by high-priced housing that could attract well-to-do suburbanites, also known as gentrifiers and, less charitably, “urban pioneers.”

More to come….

But in November 1976, the last Congress Street tenant Ray Adams refused to leave his home. With the help of neighborhood activists he successfully fought his eviction for six months. This is where the movement for affordable housing left the hearing rooms and moved into the streets. During those six months affordable housing—not gentrification—became the major rallying point in Hartford.

“They are moving the poorer people out to move the people from the suburbs in– people who have a choice already. It’s a class issue.”

–Ray Adams, Hartford artist, reluctant activist

This was not the only Hartford Process scheme for housing. In 1972 the corporate group had conjured up an $800 million, 15-year plan that would affect over 40% of the city’s population. It would create some new North End housing but ultimately eliminate a total of 2,000 housing units altogether. In fact, Process took out a $5.2 million mortgage on 1700 acres of land at a cost of $500,000 a year. The housing did not materialize.

Hartford Process shut down the Coventry “new town” effort in 1975. Under reorganized management, it finally apologized to the Puerto Rican community in 1978.

===================================

Asylum Hill, 1978

Aetna Insurance company had the same plan as Travelers in the 1950s: safe (read: white) crime-free surroundings for their buildings and employees. Picking up on the legitimate fears of local tenants and homeowners in Asylum Hill, the federally funded Hartford Institute for Criminal and Social Justice (HICSJ) was launched with millions of dollars in federal funding. Its big idea was to fence in the poorest neighborhood adjacent to Asylum Hill, known as Clay Hill. The Institute also intended to keep poor people out of the Asylum neighborhood with physical barriers.

In a very real sense, HICSJ hatched plans for a “fortress” in Asylum Hill and a “prison” for Clay Hill. The project produced little more than some one-way streets with adapted curbs, making travel by car difficult and inconveniencing the neighbors.

The Institute boasted that its work had reduced crime, but Hartford Police statistics publicly contradicted that false claim.

Brian Clemow, the HICSJ director, went on to become the number two man at Aetna.

===================================

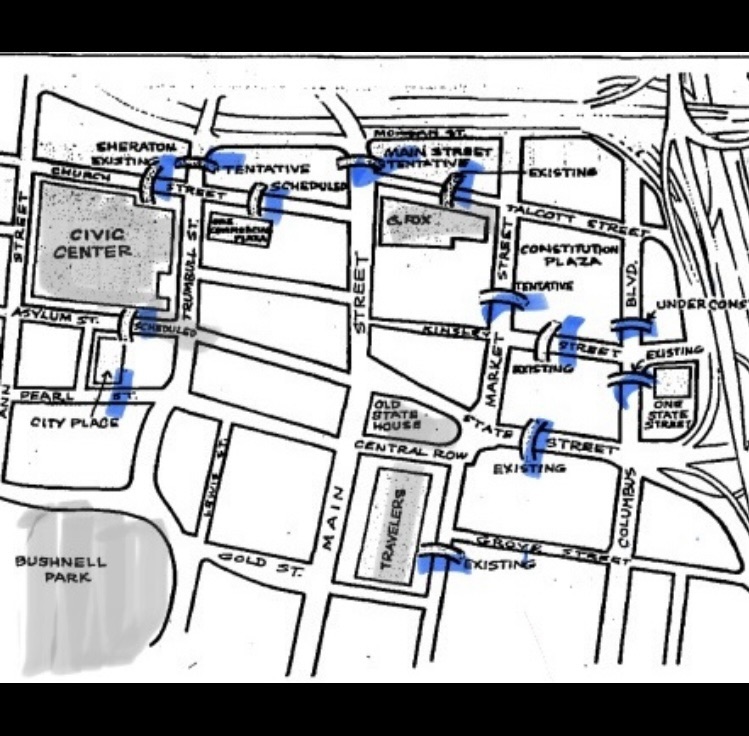

The Skywalk, 1983

Downtown was always the main focus of “renewing” Hartford. The demands of the neighborhoods were ignored. Developers and urban planners came up with a unique barrier: the Skywalk. It was designed to connect office and retail buildings from the Civic Center (now the XL Center) to Constitution Plaza.

“I don’t know who is going to benefit from this, but I suspect it is an elitist alliance between certain downtown businesses and and certain politicians.”

–State Senator Larry DeNardis (R)

In practice, shoppers and suburbanites who worked during the day and left the city by sundown would never have to touch the street. Skywalk was also envisioned as a retail outlet, offering eateries and boutique booths along the thirteen proposed glass tunnels.

Despite fierce opposition, the Skywalk was declared completed and a success. Only a small fraction of its plan, however, was actually implemented. Again, the decision makers in Hartford left out those who would be most impacted: Hartford residents who vociferously opposed the misguided project.

“Instead of providing shelter for corporate executives during a two-minute walk from one building to another, we should be building bus shelters for seniors.”

–Citizens Lobby

The first phase of this project cost $6 million (equaling $27 million in today’s dollars). The federal government offered $1.9 million from transportation funds ($8.4 million today). The money was spent by the planners even before the Skywalk was given final project approval.

“Great harm has been committed against a minority population of our society. To justify shameful acts of exclusion, and segregation.”

–Arthur Pepine, president, CT Coordinating Committee of the Handicapped

Disability activists pointed out that there no way for wheelchairs or other mobility devices for people with disabilities to use the Skywalk. Hartford’s neighborhoods were disgusted that tax dollars and millions in federal transportation money were going to be wasted instead of meeting the city’s many immediate structural and transportation needs. By 1983 the bridge in the sky was dead.

=========================

People Power grows

Hartford was struggling, but the local communities were developing their own means of political power and direct action including the Black Caucus, NECAP, Puerto Rican Socialist Party, Homefront and Save Our Homeless People (SOHPA). Neo-Alinsky organizations like HART, ONE-CHANE, and AHOP, while narrowly focused and tightly controlled, mobilized hundreds of residents on neighborhood problems.

Home-grown unions and other groups that worked to elect (or defeat) political candidates included People for Change (PFC) which built a multi-racial coalition across the city, forcing corporations, developers, and city government to respond to the needs of the people for jobs and housing.

During this time, some progress was made. The HPRO (housing, preservation and restoration ordinance) required developers to replace the homes they destroyed when building new offices. The fight for Linkage, which sought a similar goal on a larger scale, was finally defeated after Aetna Insurance boss John Filer (the big dog that led the “Bishops”) secretly criticized his colleagues who were cooperating with neighborhood representatives on this progressive ordinance.

Resistance to corporate domination continued. In 1981 protestors occupied City Hall, the state welfare office, the Hartford Hilton, and the State Capitol. Opponents of the gentrification movement disrupted a “back to the city” house tour with a massive march (which ended the annual tours).

“We have been in hotels, the Salvation Army. I’ve put my kids in foster homes to try and get on my feet. But I feel trapped. We are Connecticut refugees.”

–Barbara Crabbe, Welfare mother, activist

Hartford is still, for all intents and purposes, a one-party city: the Corporate party. But our neighborhoods and the city’s working people do not give up so easily.

Working Families Party has (WFP) has taken up the banner to support the interests of residents who would otherwise be voiceless. Connecticut Citizens Action Group fights the insurance behemoths on our behalf. Moral Mondays Hartford keeps their eyes on the prize for racial justice. Black Lives Matter has been the vanguard against police violence. Connecticut For All links our diverse struggles with a common vision. Make the Road and Immigrant Defense protect our open city. Tenant Unions and Mutual Aid Hartford point the way to building democratic power at the local level.

More information about community organizing that prioritizes people over profit can be discovered on the pages of the Shoeleather History Project, or in Good Trouble by Steve Thornton.

Please write a BOOK

How do we take these historical facts and “empower the People?” ⚖️🕊

William M. Brown

impressive. We have to connect again next year when i have history course. — Bob

Sounds good Bob!