Nancy Buckwalter and Tony Norris expected 150 people to show up at the Old State House for their event. Instead, over 300 lesbian, gay and transgender activists spent a hot June day in 1982 making history at Connecticut’s first Gay Pride Festival. Norris, Buckwalter, and their band of hard-working comrades had many reasons to be proud that day.

Nancy Buckwalter and Tony Norris expected 150 people to show up at the Old State House for their event. Instead, over 300 lesbian, gay and transgender activists spent a hot June day in 1982 making history at Connecticut’s first Gay Pride Festival. Norris, Buckwalter, and their band of hard-working comrades had many reasons to be proud that day.

It had been thirteen years since the Stonewall rebellion, several nights of street fighting sparked by a New York City police raid of a well-known gay bar. After decades of anonymity and quiet resistance, the patrons of the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street reacted to the harassment in fury. The local vice squad actually had to lock themselves in the bar for protection. Stonewall marked a turning point; activists who had been working in the civil rights and anti-war movements came home to forge the struggle for gay liberation.

Gay Pride Day was not Hartford’s first public effort for the lesbian and gay community. As early as 1965 the Greater Hartford Council of Churches was providing gay-friendly counseling through its “Project H” committee. About nine months after Stonewall, the program went public.

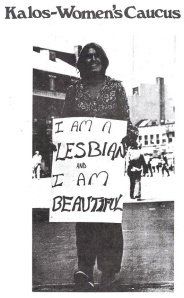

By 1968, the Kalos Society had evolved from Project H as a social organization, with the support of Episcopal Canon Clinton Jones. One of their early public events was an outing at Goodwin Park in September, 1970 (in spite of neighbors’ protests). The group quickly became the local “gay liberation front” inspired by Stonewall’s new take on social justice organizing. It published a regular newsletter, The Griffin, which was available at gay bars and in the stores at Hartford’s Union Place (known for radical and counterculture activity). The group related to politics of the left: the Griffin quoted Black Panther leader Huey Newton and sponsored a bus to a Vietnam war protest in Washington, D.C.

On September 3, 1971, eleven Kalos members were arrested while protesting at a local gay bar where lesbians were being harassed by the management. They kept up their nightly pickets until the owner capitulated.

On October 1, 1971, Connecticut became the second state to decriminalize private sexual relations between consenting adults. The effort was largely led by Hartford attorney Donald Cantor, who also worked to abolish abortion restrictions.

In 1978, the Hartford City Council was considering a measure that would forbid city departments, contractors and vendors from discriminating against people based on sexual orientation. The gay community was well- organized, with 300 supporters who packed the Council chamber at a May public hearing. A dozen “Blue Berets” (ultraconservative and often hallucinogenic Catholics) also attended. “The greatest evidence for the need for this ordinance is right here, now,” declared Rev. Jay Deacon of the Metropolitan Community Church. “It is the mindless hatred, fear, ignorance and prejudice that continues to terrorize the lives of gay persons in our society and even in our city.” Despite an affirmative 5- 2 Council vote on July 24th, Mayor George Athanson vetoed the ordinance.

organized, with 300 supporters who packed the Council chamber at a May public hearing. A dozen “Blue Berets” (ultraconservative and often hallucinogenic Catholics) also attended. “The greatest evidence for the need for this ordinance is right here, now,” declared Rev. Jay Deacon of the Metropolitan Community Church. “It is the mindless hatred, fear, ignorance and prejudice that continues to terrorize the lives of gay persons in our society and even in our city.” Despite an affirmative 5- 2 Council vote on July 24th, Mayor George Athanson vetoed the ordinance.

Back again the community came, pushing once more for a vote. Whether or not a new law would have much practical effect, this was the first time the city of Hartford–people, politicians, businesses and churches– were forced to address the fundamental principle of equal rights for all. Once more, in April 1979, the ordinance was approved by the council and vetoed by the mayor. This time, with a grassroots mobilization aimed at City Hall, defying bigots, religious fanatics, and just plain ignorance, the gay community convinced enough Council members to override the veto.

Hartford’s queer community was gaining organizing skills and building power. There were many more challenges to come.

(Thanks to Richard Nelson for his dedicated work in writing and archiving much local LGBT history.)

[…] 26th will mark 33 years since the first Pride in Connecticut. There will be a re-enactment of the Blue Berets’ picket line, something seen at the first Pride in […]

Richard Nelson has done so much to reclaim and educate us all about the LGBTQ activism in Connecticut. Thanks, Steve for adding this important part of our history/herstory to your educational pieces.