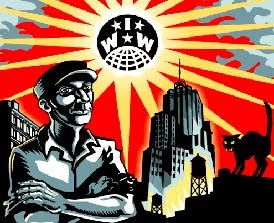

On the morning of June 27, 1905, Bill Haywood used a piece of wood as a gavel to open the founding convention of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Chicago. Later that same day in Hartford Connecticut, the State Senate voted to build an Armory for the protection of businesses located in “storm centers for anticipated riots or strikes.”

The timing was pure coincidence. The two events, however, signaled a coming collision. As Jeremy Brecher wrote in his labor history Strike! state governments built armories as fortresses in American cities “not against invasion from abroad but against popular revolt at home.”

Certainly, Connecticut’s lawmakers could not see into the future. They had no idea how threatened they would become by the IWW’s organizing efforts throughout the state. Instead, the legislators made their case for the armory by invoking the great nationwide railroad strike of 1877, the recent labor unrest in Waterbury, and earlier union strikes right nearby on Capitol Avenue. Acting in the interest of local industrialists, the elected officials argued not if the armory should be built, but where it would do the most good. Some favored a location near the state house; others said it should be built near the Colt Firearms factory. A former Hartford mayor testified he wished he had the use of an armory to protect public order in 1901 when striking machinists took over Hartford’s streets.

Certainly, Connecticut’s lawmakers could not see into the future. They had no idea how threatened they would become by the IWW’s organizing efforts throughout the state. Instead, the legislators made their case for the armory by invoking the great nationwide railroad strike of 1877, the recent labor unrest in Waterbury, and earlier union strikes right nearby on Capitol Avenue. Acting in the interest of local industrialists, the elected officials argued not if the armory should be built, but where it would do the most good. Some favored a location near the state house; others said it should be built near the Colt Firearms factory. A former Hartford mayor testified he wished he had the use of an armory to protect public order in 1901 when striking machinists took over Hartford’s streets.

By 1919, the Connecticut General Assembly had approved funding for armories across the state and had passed laws designed to curb union organizing efforts. By that time the radical IWW was shaking the very foundations of the nation’s economic system. And although the union  officially shunned the political arena, the Wobblies threatened capitalism’s hold on the electoral system as well, with battles in the workplace that spilled over into the voting booth, particularly in support of the Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs. Many Connecticut workers, poor, suffering, and powerless, would find the IWW’s appeal to take control of their own destinies very compelling.

officially shunned the political arena, the Wobblies threatened capitalism’s hold on the electoral system as well, with battles in the workplace that spilled over into the voting booth, particularly in support of the Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs. Many Connecticut workers, poor, suffering, and powerless, would find the IWW’s appeal to take control of their own destinies very compelling.

“More emphasis on property than on life”

At the turn of the 20th century, it was a dangerous proposition for a worker to join any union. You could be fired and no law existed to protect you. You could be blacklisted, and no other company would hire you. And worst of all, being a union supporter could get you beaten by employer-hied vigilantes, private detectives, the police, or even the military, as workers and organizers have discovered throughout American history. Retaliation was frequent from employers who feared losing control of their property, which meant workers as well as machines. Their prerogatives as captains of industry were also threatened. Why should they give up their wealth, status, leisure and power to a bunch of ragtag foreigners?

Here is what workers faced every day on the job in Connecticut– and around the country– during the first half of the 20th century:

The Blacklist: Companies quickly learned that union organizers, when identified by supervisors and fired, would move to another shop. The bosses maintained a list of workers they considered troublemakers and shared what they knew through their employer associations. The law was of no use to blacklisted workers. The state legislature banned company blacklists in 1911. The bosses objected and appealed. In 1912 the Connecticut Supreme Court upheld the lawmakers’ ban. But that same year it was revealed that the Connecticut Manufacturers’ Bureau kept tabs on discharged workers and communicated this information to businesses across the state. The list included the reasons for dismissal, including “wanted an undeserved increase” and “misunderstanding with the boss.” Once on the blacklist, a worker found it impossible to find new employment. Scovill Manufacturing Company in Waterbury had a formidable spy system, as did Winchester Arms in New Haven. They both kept detailed files on every worker who seemed “suspicious.”

The Blacklist: Companies quickly learned that union organizers, when identified by supervisors and fired, would move to another shop. The bosses maintained a list of workers they considered troublemakers and shared what they knew through their employer associations. The law was of no use to blacklisted workers. The state legislature banned company blacklists in 1911. The bosses objected and appealed. In 1912 the Connecticut Supreme Court upheld the lawmakers’ ban. But that same year it was revealed that the Connecticut Manufacturers’ Bureau kept tabs on discharged workers and communicated this information to businesses across the state. The list included the reasons for dismissal, including “wanted an undeserved increase” and “misunderstanding with the boss.” Once on the blacklist, a worker found it impossible to find new employment. Scovill Manufacturing Company in Waterbury had a formidable spy system, as did Winchester Arms in New Haven. They both kept detailed files on every worker who seemed “suspicious.”

Discrimination and Exploitation: Women, immigrant workers, children, and African Americans, who were just starting to become a significant part of the state’s workforce, were ignored by the traditional labor unions. They had no representation and no power. These groups comprised a significant percentage of the working class, but they were rebuffed when they knocked on the door of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the country’s largest union coalition. They could not turn to the political system either: most of these workers didn’t even have the right to vote. A study done by a special state commission in 1913 on the status of women workers found that most factories had no first aid resources even though accidents were epidemic. Toilets didn’t work and changing rooms didn’t exist. Connecticut working women totaled 49,000. More than 5,000 workers were minors. Almost 80% of the women were not married and supported themselves on wages that the commission said was “barely a living wage.”

Long hours, poverty pay: The work day ranged from 10 to 16 hours for at least six days a week. Parents and their young children worked in mills together. And still, for millions of unskilled workers, take-home pay barely fed most families. The Quidnick Mill in Willimantic was one example. Like Walmart workers today who must count on government-subsidized health care, the Quidnick workers in 1912 had to rely on public assistance even though entire families worked full time.

Deadly jobs: Matilda Cevitti worked at American Hatter and Furrier in Danbury. No effective state or federal laws required safety devices on factory machines. On April 6, 1906, Matilda was standing near a revolving machine shaft that generated static and caught her hair. The shaft ripped off her scalp and caused serious injuries to her face, hearing, and eyesight. “This is a great country for liberty, but we lay more emphasis on liberty of property than we do on liberty of life,” declared a safety expert from Hartford-based Travelers Insurance Company. He reported that across the country, two million workers were injured each year and one hundred workers a day died from industrial accidents.

Deadly jobs: Matilda Cevitti worked at American Hatter and Furrier in Danbury. No effective state or federal laws required safety devices on factory machines. On April 6, 1906, Matilda was standing near a revolving machine shaft that generated static and caught her hair. The shaft ripped off her scalp and caused serious injuries to her face, hearing, and eyesight. “This is a great country for liberty, but we lay more emphasis on liberty of property than we do on liberty of life,” declared a safety expert from Hartford-based Travelers Insurance Company. He reported that across the country, two million workers were injured each year and one hundred workers a day died from industrial accidents.

Speed ups: Always looking for methods to increase the pace of work and thereby increase profits, Connecticut employers such as the Yale & Towne Company utilized the “scientific management” method known as the Taylor system. Workers’ smallest movements were carefully measured in order to eliminate delays and speed up production. It wasn’t just efficiency the boss was after. Taylorism also had the effect of stealing the trade secrets that workers had developed to perform their jobs. By studying the work, the boss could appropriate a worker’s techniques– actually, his property– and replace him with an unskilled worker or a machine. In 1912, Congressman John Q. Tilson of New Haven spoke out against Taylorism, citing a study that found it gave managers a “dangerously high level of uncontrolled power.”

Poor housing: Living conditions were so bad in Hartford that a “sweeping investigation” was done in 1904, resulting in modest reforms. A decade later, little had changed: tenement apartments still had no running water or indoor toilets, insects infested the dwellings, garbage filled the yards and children died from the polluted water of the Park River (known as the Hog River because it was  so polluted). Landlords easily got around the zoning laws, causing overcrowding which fostered the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis and diptheria. A local minister complained that “industries are parasites and are taking lives from the country [local farms],” without creating adequate housing in the cities. Where industry did provide housing, like the Moosup textile mill, employers used it as leverage against union organizing. In March, 1906, the mill boss issued eight hundred eviction notices after the Moosup weavers went on strike.

so polluted). Landlords easily got around the zoning laws, causing overcrowding which fostered the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis and diptheria. A local minister complained that “industries are parasites and are taking lives from the country [local farms],” without creating adequate housing in the cities. Where industry did provide housing, like the Moosup textile mill, employers used it as leverage against union organizing. In March, 1906, the mill boss issued eight hundred eviction notices after the Moosup weavers went on strike.

Why would Connecticut workers join the IWW?

These conditions can certainly explain why workers would join a union to improve their conditions. But why the IWW? The Wobblies were condemned by clergymen, outlawed by politicians, lied about by the press and attacked by the police. Even the term “Wobbly,” a nickname with an unclear origin, seemed strange.

There were at least two reasons workers were attracted to the IWW. First, unskilled workers were largely ignored by the traditional craft unions. The dominant voice of labor was the AFL and its president Sam Gompers, who ran the coalition for thirty-eight years. The federation was comprised of craft union members, skilled white males who jealously guarded their own benefits to the exclusion of all others. The IWW called the AFL the “American Separation of Labor” because the group could not even get its constituent unions to cooperate with each other against common employers.

Workers turned to the organization that had as its principle “one big union” of all working people. The IWW projected “a vision of a really democratic society,” not one where plutocrats ruled the economy, according to historian Paul Buhle. “Decentralized democracy, democratic decision-making at all levels, is the most radical idea ever hatched in North America and the only one with real lasting appeal.”

Workers turned to the organization that had as its principle “one big union” of all working people. The IWW projected “a vision of a really democratic society,” not one where plutocrats ruled the economy, according to historian Paul Buhle. “Decentralized democracy, democratic decision-making at all levels, is the most radical idea ever hatched in North America and the only one with real lasting appeal.”

There was another reason the IWW attracted unorganized workers, less tangible but just as important. The Wobblies offered the workers a new labor culture, one that included them and respected their own languages and traditions. It was a culture that sang to them.

The Wobs had their own celebrities, brazen figures like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn who could mesmerize thousands at a mass rally. They had their own troubadours, like Joe Hill who lampooned hypocrites in high places and cut them down to size. The IWW had its own sound track, with scores of tunes sung from the “Little Red Songbook” that kept up workers’ morale in dark times. Songs like Solidarity Forever are still sung at union meetings, even though many workers don’t know it came first from the Wobblies.

The Wobs had their own celebrities, brazen figures like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn who could mesmerize thousands at a mass rally. They had their own troubadours, like Joe Hill who lampooned hypocrites in high places and cut them down to size. The IWW had its own sound track, with scores of tunes sung from the “Little Red Songbook” that kept up workers’ morale in dark times. Songs like Solidarity Forever are still sung at union meetings, even though many workers don’t know it came first from the Wobblies.

Immigrants didn’t have to change their names and lose their accents to join the Wobblies. They were welcome to join as themselves, and the union adapted to them with newspapers in a dozen languages, interpreters at meetings, and organizers like Joe Ettor, who looked and dressed as if he could be an a Italian cousin who just landed at Ellis Island.

The Wobblies communicated through “silent agitators,” small stickers with pithy ideas. They could boil down big concepts into highly potent weapons. “An Injury to One is an Injury to All,” they declared. “We will build a new society within the shell of the old.” “One Big Union for all workers.” IWW organizers were ready to sacrifice their comfort, safety, and their lives to make those slogans a reality.

The Wobblies communicated through “silent agitators,” small stickers with pithy ideas. They could boil down big concepts into highly potent weapons. “An Injury to One is an Injury to All,” they declared. “We will build a new society within the shell of the old.” “One Big Union for all workers.” IWW organizers were ready to sacrifice their comfort, safety, and their lives to make those slogans a reality.

The following stories tell the tale of what workers discovered in themselves when they joined the Wobblies, and how much they endured in order to become IWW members in Connecticut’s mill and factory towns.

Despite the destruction of records from police raids and internal splits, much of the IWW’s history has been documented. Still, very little research on Wobbly organizing has been done in Connecticut. According to the Hartford Trade Board, Hartford had “wholly escaped the contagion [of] any rash agitator who should attempt to disturb the harmony” of the city. Historians have quoted this business group’s glib assurance as proof of labor peace, but the record tells a different tale.

From: A Shoeleather History of the Wobblies — Stories of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Connecticut; by Steve Thornton, (Red Sun Press, 2013)

Another great article Steve

Great article, fellow worker, and timely. I love reading your work!Solidarity, PaulaPaula de Angelisscholar, freethinker, educator