What would have happened if Bartolomeo Vanzetti had found work in Hartford? He traveled to our city, probably in 1909, looking for employment. According to his biography, Vanzetti found some kindness, but no work, and frequent resentment and discrimination due to his Italian origin. Within a few years, this self-described “poor fish peddler” and his friend, a shoe maker named Nicola Sacco, would be on trial for their lives in Massachusetts. The worldwide fight to save them, and their eventual executions on August 23, 1927 touched the lives of people in Hartford and around the world.

Bart Vanzetti came to America from Villafelletto, Italy in 1908. Nick Sacco arrived in the same year from Torremaggiori. They met in 1917. Like thousands of other immigrants, they left their country, as Vanzetti wrote, for “a little land to grow, a roof, and some books.” Thanks in large part to their experiences in this country, they became anarchists and labor organizers, both highly unpopular ideas in polite society. Neither of them had ever done anything remotely violent to promote their cause. But on the night of April 15, 1920, someone robbed a payroll master in South Braintree, Massachusetts, leaving two guards dead.

Bart Vanzetti came to America from Villafelletto, Italy in 1908. Nick Sacco arrived in the same year from Torremaggiori. They met in 1917. Like thousands of other immigrants, they left their country, as Vanzetti wrote, for “a little land to grow, a roof, and some books.” Thanks in large part to their experiences in this country, they became anarchists and labor organizers, both highly unpopular ideas in polite society. Neither of them had ever done anything remotely violent to promote their cause. But on the night of April 15, 1920, someone robbed a payroll master in South Braintree, Massachusetts, leaving two guards dead.

In the rush to find the killers, police eventually arrested Sacco and Vanzetti. According to Felix Frankfurter (who later became a Supreme Court justice), the trial was a travesty. The prosecution misrepresented evidence and ignored important facts. The pair had a hanging judge on the bench, Webster Thayer, who told an acquaintance “Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards?”

America in the early 1900’s was a dangerous place for labor organizers and people with left-wing views. Unbridled economic exploitation caused strikes by textile workers, steelworkers, and even the Boston Police. This agitation in turn triggered the creation of the American Legion and the FBI in order to defeat the menace of red bolshevism.

Hartford industrialist Clarence Whitney pledged $50,000 to “investigate and infiltrate local unions” influenced by the Connecticut Federation of Labor and the “Bolsheviki.” The infamous Palmer Raids, led by the U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and his young assistant J. Edgar Hoover, led to the arrests of almost one hundred Hartford-area men, many of whom were deported solely due to their political beliefs or affiliations.

Hartford industrialist Clarence Whitney pledged $50,000 to “investigate and infiltrate local unions” influenced by the Connecticut Federation of Labor and the “Bolsheviki.” The infamous Palmer Raids, led by the U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and his young assistant J. Edgar Hoover, led to the arrests of almost one hundred Hartford-area men, many of whom were deported solely due to their political beliefs or affiliations.

In 1927, as their defense appeals failed, protests spread in support of Sacco and Vanzetti. Hartford was no exception, despite local government and law enforcement attempts to squash dissent. More than 800 union members met in Scheutzen Park on July 31st for a picnic that turned into a support rally. They heard speakers denounce the shoddy and secretive methods used to secure a conviction. One featured speaker was William Z. Foster, a labor leader who would eventually become the head of the American Communist Party. The assembly unanimously passed a resolution expressing their class solidarity with the pair and urged the governor of Massachusetts to revisit the case “in the name of justice America prides itself on.”

As the execution deadline approached, strikes and riots broke out throughout the country and around the world. It became impossible for Sacco and Vanzetti’s local supporters to voice their public opposition to what they considered a frame-up. The simple act of handing out leaflets triggered swift action by the police and the courts. Seventeen-year old Sonia Epstein found she had warrants issued for her arrest in both Hartford and New Haven for leafleting in those cities. She was finally arrested with four others on August 7th. The police insisted that content of the handbills had nothing to do with their arrests. It was simply against the law to distribute literature without a permit, the authorities insisted.

When Hartford teenagers Albert Epstein and Nathan Hurvitz (15) tried to get a permit for two outdoor protests, they too were rebuffed by Hartford’s Mayor Stevens who said he was taking no chances on possible disorders, “no matter how harmless” the petitioners looked. No outdoor demonstrations took place, but hundreds did gather at Unity Hall on Pratt Street on the evening of August 22nd to wait for the news they were dreading.

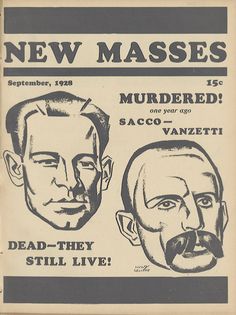

Shortly after midnight on Tuesday, August 23, 1927, Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco were electrocuted. Protests, however, did not end with their deaths. Hartford union members organized a local memorial service and a contingent of activists traveled to Boston for the funeral. Police reaction continued as well. Two New Britain men decorated their car with signs decrying the executions and drove down Hartford’s Main Street on the Sunday after the executions. They too were promptly arrested for not having a permit to display the signs.

Shortly after midnight on Tuesday, August 23, 1927, Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco were electrocuted. Protests, however, did not end with their deaths. Hartford union members organized a local memorial service and a contingent of activists traveled to Boston for the funeral. Police reaction continued as well. Two New Britain men decorated their car with signs decrying the executions and drove down Hartford’s Main Street on the Sunday after the executions. They too were promptly arrested for not having a permit to display the signs.

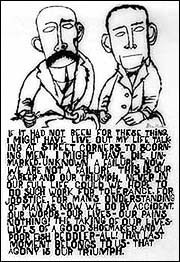

Controversy continues today over Sacco and Vanzetti’s guilt or innocence. But there can little debate about the impact of their executions on the movement they came to represent. The death of the two martyrs was a lesson on how seriously the status quo takes challenges to its authority. Trade unionism and critiques of capitalism were faced with unyielding hostility and defeat. Not until the Great Depression plunged millions into poverty was there another fundamental challenge to the economic system that was failing working people and immigrants.

And the winners? Several Hartford insurance companies were reported to have written a quarter of a billion dollars in “civil commotion, explosion, and riot insurance” policies thanks to the nationwide protests against the executions.

The fight to save Sacco and Vanzetti had an undeniable effect that Judge Webster Thayer never intended. At least two of the Hartford activists involved in defense efforts learned valuable lessons that eventually contributed to their national reputations as labor leaders. They were Leon Davis, a young Jewish immigrant who emigrated to Hartford from Russia, and Ernest DeMaio who lived on Mechanic Street in the city’s Italian neighborhood. DeMaio eventually became a leader of the United Electrical workers union. Leon Davis went on to build the New York hospital workers’ union known as 1199.

Both men succeeded in organizing workers despite red-baiting and government opposition to their efforts. Their unions continue today as vital organizations fighting for social justice, a testament to the training they received in Hartford’s struggle to save the lives of the poor fish peddler and the good shoemaker.

My father Nathan Hurvitz was 15 years old at the time. 15, imagine that.